The Women of Whitechapel: The untold stories

Between August and November in 1888, Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly were murdered in London’s Whitechapel by the most famous serial killer in history, Jack the Ripper.

130 years after these tragic deaths, Iain Bell’s brand-new opera, Jack the Ripper: The Women of Whitechapel gives a voice to the often-nameless victims.

Ahead of the opera’s world premiere, find out more about the lives of the five women.

Mary Ann ‘Polly’ Nichols

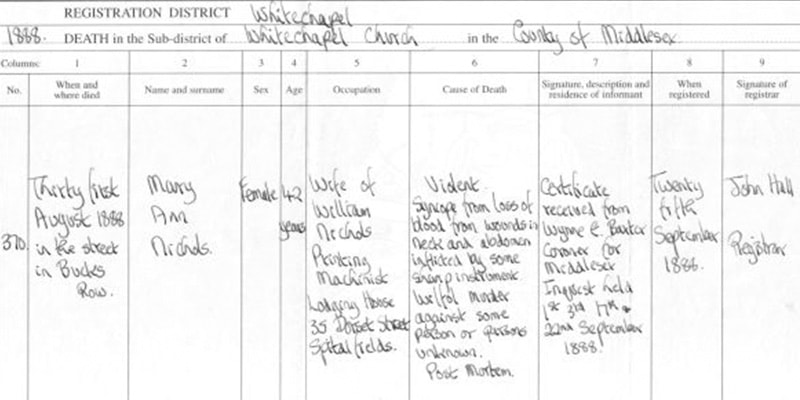

Polly Nichols’s death certificate.

Born 26 August 1845, Polly Nichols was the middle child to Edward and Caroline Walker. Unlike many working class girls of the time, Polly studied at school until she was 15, and so not only did she learn to read, she could write too.

Although not all of them survived infancy, Polly had 6 children with William Nichols. Unfortunately, the breakdown in her marriage with William resulted in Polly turning to the workhouse for food and a roof over her head. Many people who entered the Victorian workhouse found themselves in a cycle of poverty, one very few could break. During this time, Polly turned to alcohol to comfort. Unfortunately, this dependence on alcohol would be detrimental to Polly, as it was for many destitute woman of the time.

On the night of her death, 31 August 1888, Polly had spent her doss house money at the pub, and found herself drunk and without shelter for the night. This situation, however terrible, would not have been uncommon. She died on the streets of Whitechapel, aged 43.

Annie Chapman

Hanbury Street as it was at the time of Annie Chapman’s murder. In the centre of the photograph is 29 Hanbury Street. This is the door through which entry was gained into the backyard where her body was found.

Annie Eliza Smith and her five siblings received an education far superior than many working-class children of the time, thanks to their Father’s position in the army.

In the spring of 1844, a scarlet fever epidemic spread through London. In the space of three weeks, Annie’s parents would lose four of their 6 children.

At aged 20, Annie, like the majority of working-class young adults, was expected to work to begin contributing to the family income. At 27, Annie married John, the couple had two children. Thanks to her husband’s well-paid job as a gentleman’s coachman, Annie and her family were able to live comfortably and send their children to decent schools. They might have continued to live this relatively comfortable life for good, had Annie not been an alcoholic. Due to her alcoholism, 6 of her eight children died in infancy, something which no doubt fuelled her need to drink more.

Unable to give up alcohol, Annie was forced to leave her family, and eventually found herself in Whitechapel. At the time of her death, she was destitute and suffering with tuberculosis.

On the night of 7 September, Annie Chapman found herself wondering the streets drunk and alone, having been kicked out of the doss house she regularly stayed out for spending her lodge money on beer. She died aged 47.

Elizabeth 'Liz' Stride

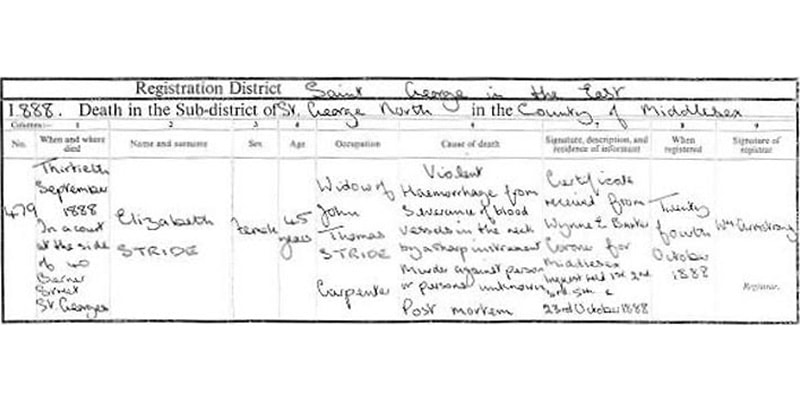

Death certificate of Elizabeth Stride.

Aged just 22, Elisabeth Gustafsdotter (she later anglicised the spelling of her name), having being shunned from society for the birth of her illegitimate child and involvement in prostitution, decided to leave Sweden behind for a better life in London.

At 25, now living as a housemaid in London, she married John Stride, a man nearly double her age. The couple soon opened their own coffee house in Poplar. Unbeknownst to John, Elizabeth had syphilis, a disease which gave high risk of miscarriage and stillbirth. It’s likely this is the reason why the couple never had children. With the collapse of their business, plus the inability to conceive together, Liz and John’s relationship began to break down. She turned to drink.

By the end of the summer of 1888, months before she died, she had been arrested for being drunk and disorderly no fewer than four times. In her final years, Elizabeth lived a secretive life, which is why little is known about her movements on the night of her death.

Unlike the first two victims, it is thought Elizabeth had the money to pay for her lodgings for the night, so expected to return when she ventured out for the last time on 29 September. She was 45.

Catherine ‘Kate’ Eddowes

Illustration of Kate Eddowes being found in Mitre Square from The Illustrated Police News, 1888.

Kate Eddowes, was originally born in Wolverhampton although her family moved to London when she was just 9 months old. She was one of 12 children.

Having been chosen by her parents to receive proper schooling at a respectable school, Kate might have been able to carve a decent life for herself once her education had finished. That was until her parents both tragically died. For reasons unknown, following the death of her parents, Kate’s siblings decided that she should be the one to start a new life back in Wolverhampton, and so, in December 1857, Kate was sent on a train to live with a family she had never met before.

Five years later, aged 20 Kate found herself pregnant with her first child. Pregnant Kate and her partner, Tom moved to Birmingham and began performing and writing poems together. The couple travelled the country in search for success, striking gold in Staffordshire with a hanging ballad about a distant cousin. With the riches from the successful ballad, Kate and Tom decided to make their move (back) to London.

Life in London was especially tough for the working classes, and Kate’s life was no different. Struggling to find work, and stuck in an abusive relationship, she soon found herself in and out of workhouses and (thanks to her dependence on alcohol) in the police station too.

On the night of her death, Kate had been arrested for drunkenness, and was taken to the police station to sober up. Five hours later, the police officer on duty thought her sober enough to be kicked out onto the streets of Whitechapel. It was 1am. With no money for a roof over her head, 46-year-old Kate laid down to sleep in Whitechapel’s Mitre Square. Her mutilated body was discovered before 2am that same night.

Mary Jane Kelly

Whitechapel, Dorset Street, Miller’s Court No.13. Photograph taken the day of the murder of Mary Jane Kelly of the outside of her room.

Little is known about Mary Jane’s childhood. It is thought that the many different stories she told about her life were largely fictitious. What we do know is that she arrived in London’s West End at some point between 1883 and 1884.

As a courtesan, she briefly spent time in Paris, before hastily returning to London’s West End to continue her trade. It is thought that Mary Jane was tricked into visiting Paris and most likely would have fallen victim to sex trafficking, had she not so quickly returned to London.

By October 1888, Jack the Ripper’s killing spree was the talk of Whitechapel. Working class women in the sex trade especially were anxious to be out at night alone. Mary Jane, herself concerned about the murderer, offered up her home to vulnerable women. Inviting strangers to stay in the house, although an act of compassion, was the final straw for her partner Joe Barnett. On 30 October, he moved out of their house.

On 8 November, Joe visited Mary Jane at their house. The glass window at the front of the house, which had been shattered by Mary Jane in an alcohol-fuelled rage some weeks before, was plugged closed with rags. He left her and she was later seen with a man later that night. At some point in the early hours of the next morning, Mary Jane Kelly quietly slipped back into her own bed. None of her neighbours heard her brutal murder take place. She was 25.

Bell’s Jack the Ripper: The Women of Whitechapel is at the London Coliseum from 30 Mar – 12 Apr 2019. Find out more and book tickets below.