ENO Response: The Mikado reviews

8th November 2019 in News

ENO Response is a new scheme that gives aspiring journalists and reviewers the opportunity to produce opera reviews and receive writing advice and feedback.

ENO has had no editorial input in the reviews. All views are their own.

Olivia Clark

This year’s production of The Mikado is an opera not to be missed. This classic was jointly created by the writer W.S Gilbert and Composer Arthur Sullivan. Elaine Tyler Hall, (the director of this revival), managed to bring to life the Jonathan Miller production (the director of the 1986 production of The Mikado) that encapsulates the jaw aching and rib hurting humour that Gilbert and Sullivan’s work is well known for.

The power of the drums during the first few seconds of the introduction directly led us into the intimidating power of the Mikado himself. Then we were brought into a light-hearted sequence that set the tone for a very British Japanese Town of Titipu (where the Opera is set). Where simultaneously, the dark blue/purple lights surrounding the dome above us built on the music itself thanks to the revived lighting designer Marc Rosette.

Stefanos Lazaridis set design for the 1920 English hotel in Japan, along with the decision for the characters in the production to speak and sing in an upper-class accent was a great way of conveying the social commentary on the ridiculous laws that were put in place in the Victorian era. In the program Andrew Crowther (the Biographer of W.S.Gilbert) mentioned that it was during this time the Lord Chamberlain’s office had the power to censor what the UK theatrical performances due to The Licensing Act of 1737 thus “unofficially censoring public opinion” (Crowther, 2019) on anything seen immoral behaviour. This is similarly seen in The Mikado as the “no flirting” Law.

The continuation of Stefanos Lazaridis 1920’s style set design, is a combination of serial and art deco movement which was playing with your perspective. The lower stage right of the set was like an optical illusion as the slope gave the impression of a much longer and wider ‘hallway’ which was put to good use when you saw the maids and bellboys perform various activities which were part of their duties. The use of this 1920’s set I think helps capture the unreal events that are happening in the Opera such as their names, the over the top personalities or even observing the funny touches such as: watching the drunk maid stumble out one of the doors looking rather “dishevelled” (Suart,2019) followed by a bellboy carrying towels to clean up her mess as if nothing happened.

Watching the performance, I felt that the cast had great fun performing. You could see that they played around with their character and each other, particularly when Yum-Yum’s (Soraya Mafi) hat got knocked off her head, at the end of the ‘three little girls’ song Pitty-Sing (Sioned Gwen Davies) managed to smoothly to hand it back afterwards quickly whilst remaining in character.

I love how in each new revival of The Mikado, KoKo’s aria about his ‘little list’ is very aware of current social and political attitudes. This year, his speech about was climate strikers protesting all over London’s High street, fake lovers of curly kale, Jacob Rees-Mogg. Which is a great way of making fun of our time of political uncertainty.

It was a great decision on behalf of the costume designer Sue Blane to mainly stick to a black and white colour palette for the 1920 style costumes, rather brightly coloured Kimonos. Not only do the white and black garments worn by the performers look more in tune with the set, the playful atmosphere that we tend to think of when we look back at the 1920’s (especially combined Anthony van Laast hyper-energetic choreography) and it draws us back on the idea that W.S Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan were making a comment on the censorship of theatrical performers. Moreover, if they were to put a predominantly white cast in a variety of brightly coloured Kimonos, they would be appropriating someone else’s culture which I don’t think is something to be taken lightly. Which I don’t think the ENO is about, and on this note, the karate moves made by the ‘the gentlemen of japan’ and the schoolgirls were untasteful, it goes back to the idea of it seemed off that a grown adult would do something like that. I also didn’t see the use of KoKo (Richard Suart) holding the Luofa, the prop seemed out of place and kind of forgotten about in the mini-water fountain.

All in all, this light-hearted performance surpassed my expectations, it will leave you laughing for days afterwards and I highly recommend everyone go see it.

Patrick Shorrock

It was something of a shock to realise that I first saw Jonathan Miller’s production of The Mikado in 1986, when people were deeply shocked at the way Miller ditched the fake Japonaiserie and made what has been regarded as a theatrical dinosaur fun and elegant. So effective has Miller’s production been in changing our expectations of Gilbert and Sullivan, that it has transitioned from iconoclastic to classic, and now seems utterly conventional. Was it really so radical to put on an operetta with an excellent cast and turn it into a glamorously ritzy west end musical – complete with tap dancing (excellent choreography created by Anthony Van Laast), fabulous 1920s costumes (Sue Blane) and a superb set by the late great Stefanos Lazaridis in his white period that also gave us the stunning Magritte inspired Rusalka, a totally new production of which is due later in the season.

To be perfectionist about it, the production’s emphasis on making the big well-known numbers as big as possible – and they all generate bags of applause – is slightly at the expense of dramatic momentum and coherence between the numbers, even though the dialogue is expertly well delivered by masters of the art such as Richard Suart’s Koko and Andrew Shore’s Pooh Bah. Dressing the maids from school in St Trinians costumes is a masterstroke, but slightly undermined by musing on why on earth they brought the lacrosse rackets to an hotel, other than to have an opportunity to wave them stylishly about in one number and have them gathered up in the next.

To be brutally honest, Charles Court Opera’s minimal version with piano and no chorus at the King’s Head had more dramatic bite and conveyed more poignantly the underlying melancholy beneath the surreal clowning.

But, carping aside, this is a very classy show with much to enjoy. It is a treat to hear Sullivan’s superb music played by a first rate orchestra under Chris Hopkins and sung by top notch voices, with a former Wotan – Sir John Tomlinson no less – with a voice and personality as big as his fat suit in the title role. Andrew Shore provides a suitably Sir Humprheyesque Pooh Bah, and Richard Suart, seems to have been playing Koko forever, although my memory suggests it was Eric Idle who did the honours in the first run of the production. Yvonne Howard is a stylish Katisha but needs to be more Joan Crawford and less Prue Leith. She sings beautifully, but lacks bite and incisive musical phrasing, even if you lay aside memories of the incomparable Felicity Palmer in this role. Splendid newcomers. Elgan Llyr Thomas and Soraya Mafi have beautiful voices and musical phrasing that enables them to make a big impact in A Wandering Minstrel and The Sun and I, but their sound would have been even more gorgeous if they hadn’t been required to put on sub Wodehouse silly ass voices.

It’s easy to chafe against the cosiness of some of Gilbert’s satire, which can be seen as ineffective, whether because of the impregnability of its targets – the House of Lords is very much still with us despite Iolanthe – or the fact that they are constants of human existence – whether the idiocies of young love or the slow running of suburban trains. It is practically a badge of honour to be included in Koko’s list of things that would not be missed, which featured Dominic Raab, Boris Johnson, Jacob Rees-Mogg, Daily Telegraph and Mail readers – soft and easy targets all – and then, in the interests of balance and a ready rhyme, climate activists, John Bercow and the politically correct. Interestingly, subtitles were not provided. I suspect that this is to enable the words to continue to change and develop throughout the run and allow for spontaneity rather than a requirement of the libel lawyers.

The Mikado is revealed by Miller’s production to be an exploration of the nature of Englishness – stylish, ridiculous, evasive, and ironic, but with an undertow of suppressed melancholy. Gilbert is parodying ruthless social ambition, venality and hypocrisy and the arbitrariness of social conventions, but these are things that the characters are willing to admit to when cornered. They are much more evasive – as are we all – about their fears of death and rejection, although Sullivan’s music whilst fizzing with surface silliness captures this underlying sadness beautifully.

This slick show is much better at the former than the latter.

Aine Kennedy

The Mikado breezes onto the stage of the Coliseum like a refreshing spritz of your nan’s eau de cologne. Jonathan Miller’s production really is the grand dame of the season, appearing in its umpteenth revival since 1986: it’s comfortingly familiar, timelessly classy, and occasionally reminiscent of those awkward holiday moments when Great Aunt Edwina starts on gay marriage. It may not be an Orpheus, but this production asks as much of its audience as the rest of ENO’s autumn programme- for its backwards rather than forward-looking tendencies.

The current season at ENO has been dominated by the Orpheus series, four versions of the classic myth that have veered sharply into the realm of the experimental as they attempt to tease out the meaning of the story across centuries of Western history. This Mikado feels somewhat like an attempt to balance the scales in one fell, 1930s-style swoop, grounding the postmodern pull of other productions with a flurry of kiss-curls and perfect cadences. It’s a tried and true formula that “has long been a hit with theatre-goers of all ages”, in ENO’s own words, but this supposedly light opera isn’t quite as blithe as it might seem.

Stefanos Lazaridis’s set conjures an English seaside hotel, a nod to the distinctly un-Japanese character of the opera, whose supposedly remote and oriental setting veils a commentary on blatantly British affairs. Now, as at the time of its 1885 premiere, The Mikado invites its viewers to interpret its fantastical cast of corrupt politicians, bumbling old lechers, and vain, unworldly schoolgirls through the lens of real life. Although the production proved rich with tongue-in-cheek nods to the turmoil seething a 15-minute drive away at the Palace of Westminster, it chose not to explore them in particular depth, despite being billed as a “fantastically familiar” take on Titipu’s “fake (and) fatuous” political milieu. It’s an interesting paradox: by programming a biting satire as the most accessible item in the season, ENO has set itself the considerable challenge of staging a political opera without being too political.

Take, for example, the 1930s setting, which provided context for stunning dance and slapstick routines from an army of well-heeled maids and bellhops, strongly reminiscent of golden-age Hollywood. Anthony van Laast’s choreography provided the perfect visual accompaniment to the trim, elegant elaborations of the score, which treads the line between prim Victorianism- with its diligent, rather predictable patterns of harmony and sequence- and a more coy, flirtatious side, as the apparently inoffensive music quietly subverts hypocritical British morals. The high-kicks and flying feather dusters delighted the children in the audience, and provided a welcome distraction, as the score looped back to yet another repetition of yet another jolly waltz-type theme in seemingly every chorus and aria. However, this giddy, unadulterated nostalgia for Merrie Olde Englande- realised in detail at every level of the production, down to the plummy tones of the cast, belting out ‘Miya Sama’ in impeccable Received Pronunciation- felt somewhat incongruous with the occasional bursts of ardent ‘wokeness’.

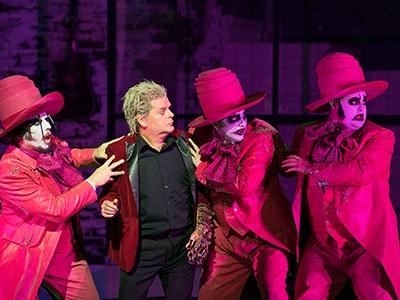

Richard Suart’s Ko-Ko was a masterful comic force, honed to perfection by decades in the role; he is also in the habit of rewriting the ‘little list’ aria to “satirise topical issues and figures”. This evening’s iteration further demonstrated the reluctance of the production to commit too fully to either the Guardian or the Telegraph readership in the audience- although the relative size of both could be determined by the varying responses to the names dropped. Suart’s lampooning of Boris, Rees-Mogg, and the Attorney General elicited enthusiastic guffaws that threatened to drown him out at times. Extinction Rebellion? John Bercow? The Sussexes? Crickets. Or at best, an uncomfortable giggle. The artistic skill of Suart’s performance was rivalled by Soraya Mafi, following up her standout performance as Love in Orpheus and Eurydice with a show-stealing Yum-Yum; the richness and authority of her soprano was matched only by that of John Tomlinson’s Mikado.

The Mikado is a means of political commentary through art, as evident in its opening lines: ‘we are gentlemen of Japan,’ sing the chorus, ‘on many a vase and jar, on many a screen and fan’. They are not literal Japanese people; they are an artistic reflection of Victorian attitudes. Racist as it may be— unsurprisingly, ENO’s production used a version of the libretto altered to remove repeated instances of the n-word- the opera is ripe with opportunities for meaningful social commentary, which require a more direct confrontation with its historical and political qualities, in both past and present contexts.