A Guide to the Slavic Folklore of Rusalka

Did you know that Antonín Dvořák’s opera Rusalka is based on Slavic folklore? Not the titular entity, but several mythical beings that stalk the woods of legends turn up in our foray into Dvořák’s best-known opera.

Read on to find out more about the supernatural figures you may encounter in the world of Rusalka.

Rusalka

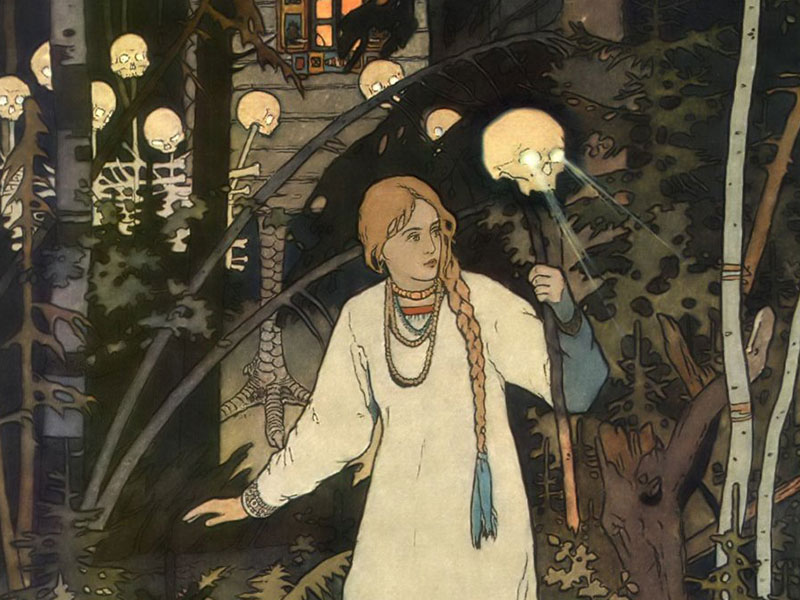

The titular Rusalka is based on the entity of the same name from Slavic Mythology, but unlike many modern depictions, the Rusalka is not a mermaid – it has legs. Appearing entirely female, the Rusalka was originally a term used by Slavic pagans for fertility wights (a term for a spirit, ghost, or other supernatural being) that passed water to their crops and fields to nourish them.

This benevolent portrayal changed in the 19th century, when the myth changed to reflect a more cynical, malevolent world view: the Rusalka of this time was thought to be ‘unclean’ by definition, thought to have arisen by a woman drowning in a body of water, either by way of suicide or murder.

Dvořák’s depiction mostly utilises the earlier depiction, beginning as a peaceful water nymph, akin to the fertility spirits of early Rusalka folklore. However, the duality of the historical Rusalka comes in the play in Act 3 of the opera, where her beloved Prince has rejected her for the Foreign Princess – Rusalka turns into a bludička, a ‘spirit of death’, also known as a ‘will o’ the wisp’.

In this form, Rusalka lives in the depths of the lake, only emerging to drag humans to their deaths. Her ending is just as grim, fulfilling her lover’s request to die by her kiss, returning to the depths in sorrow.

Rusalka will be played by Corinne Winters in the 2020 London opera production of Antonín Dvořák’s Rusalka.

Vodyanoy – Water Spirit/The Spirit of the Lake

Also known as Vodnik, the Water Spirit of Dvořák’s opera is better known in folklore as Vodyanoy (amongst other names, such as Wassermann or Nix). Dvořák appeared to be particularly fond of this Water Goblin, writing a separate symphonic tone poem titled Vodník.

Hailing from Slavic, German and Czech’s shared folklore, Vodyanoys were often depicted as humanoids with toad-like features, such as gills, webbed fingers, a greenish hue and anuran features. Usually found riding along the river on a half-sunk log, the Vodyanoy were generally viewed as elderly old men, in stark contrast to the youthful feminine Rusalkas.

Whilst not necessarily viewed as malevolent, Vodyanoy (along with Rusalki) were often blamed for drownings, with the Vodyanoy storing the souls of the drowned in teapots. Usually thought to be pretty lazy, they pass the time by playing cards, smoking pipes, and watching the water pass by.

In Dvořák’s Rusalka, the Water Spirit is Rusalka’s father, acting as her consciousness for much of the opera, and a character of caution. He warns the titular heroine against dealing with Ježibaba, as repercussions will undoubtedly follow. Unfortunately for our protagonist, the Water Spirit is proven right, leading to the Prince’s betrayal and her downfall.

The Water Spirit will be played by David Soar in the 2020 production of Antonín Dvořák’s Rusalka opera.

Baba Yaga – Ježibaba

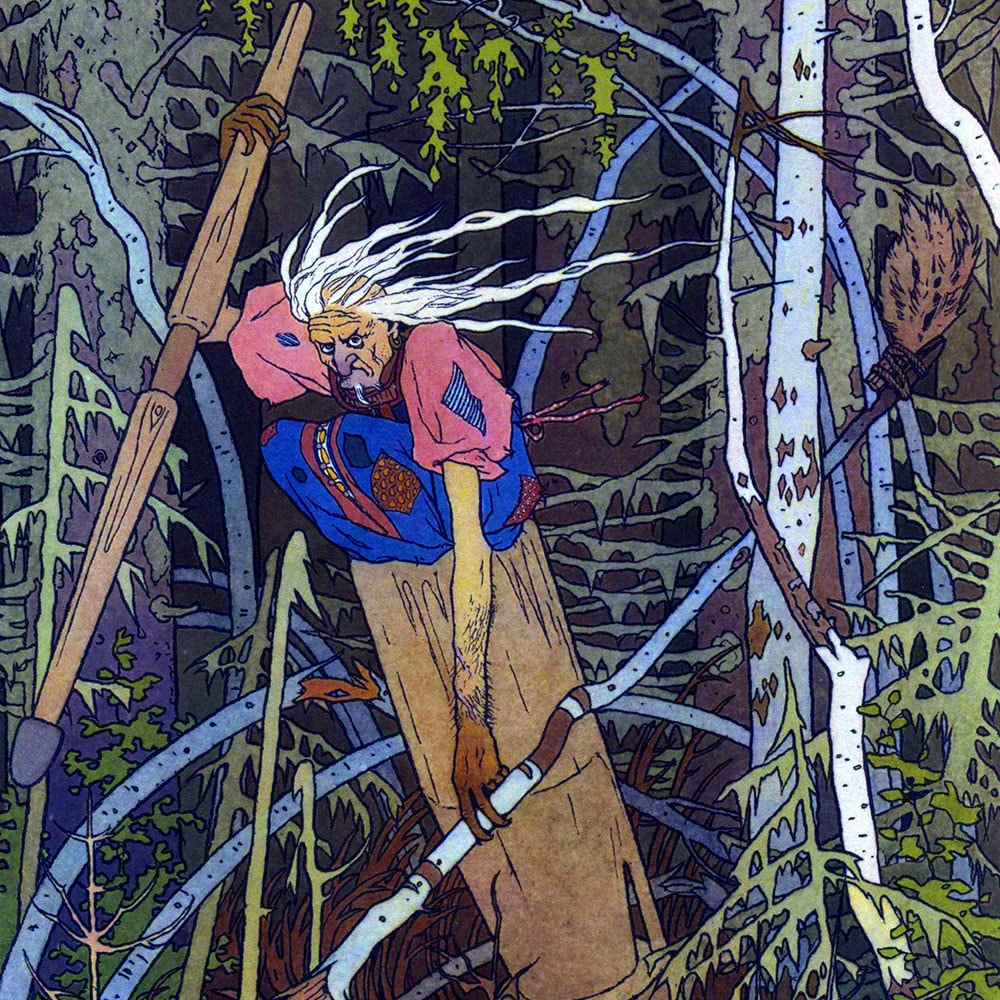

Whilst the word Ježibaba loosely translates to ‘crone’, the folklore figure associated with this character is more commonly known as Baba Yaga, a famous legend in herself. A well-known figure in Slavic/Russian folklore, Baba Yaga is one of a trio of ferocious witches, and usually is of ambiguous morality, following her own wants – whether they line up with the protagonist or not is entirely coincidental.

‘Baba’, in its original form, means sorceress/fortune teller/midwife (later used as the root of the modern Russian word ‘babushka’, grandmother), giving a good indication in many stories she appears in. Embodying the mythological archetype of the totemic matriarchal ancestress, Baba Yaga is usually the supernatural figure that changes the trajectory of the protagonist’s life, usually leading to a ‘careful what you wish for’ moral lesson, typical of folklore and fables.

This is no less true in Rusalka: our titular heroine seeks the help of Ježibaba for assistance in becoming human/mortal when she falls in love with the Prince. As part of Ježibaba’s bargain, she loses both the power speech and her immortality, as well as the proviso that the Prince will die if Rusalka does not get the Prince to fall in love with her.

When all does not work out well for Rusalka’s relationship with the Prince, she returns to Ježibaba, who decrees she can save herself, if only she kills the Prince with a dagger. Whilst Rusalka refuses, the Prince seeks his own demise by her hand when she has become a spirit of death. In this way, Ježibaba is the central dramatic character of the opera, whose actions dictate the drama that follows Rusalka throughout.

Ježibaba will be played by Patricia Bardon in the 2020 production of Antonín Dvořák’s Rusalka.