ENO Response: Carmen reviews (Part II)

6th February 2020 in News

ENO Response is a new scheme that gives aspiring journalists and reviewers the opportunity to produce opera reviews and receive writing advice and feedback.

ENO has had no editorial input in the reviews. All views are their own.

Alex Grant-Said

There’s a sigh of relief as Carmen appears on the Coliseum stage. She’s a testament to good casting, sultry and hypnotic with every motion. But Calixto Bieito isn’t interested in 19th Century archetypes or flamenco spirit.

Dubbed the “Quentin Tarantino of opera,” his provocateur reputation precedes him. This is the same director who famously opened Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera with politicians defecating en masse. Within minutes our performer melts back into a chorus of factory girls, an inexplicable red herring, replaced by the decidedly more awkward figure of Justine Gringyté wheeled out in a peepshow telephone box.

One can’t help but feel sorry for the mezzo-soprano. Already undermined by a confusing entrance, you can practically hear the director’s shouts of “more, more!” as she grinds relentlessly against Don Jose’s crotch, bares her bra and whips off her knickers.

The overblown physicality is more suited to parody than passion and combined with Gringyté gurning through an uneasy Habanera, her performance leaves little room for allure. Any suggestion that the mezzo soprano’s vocals, competent if a touch two-dimensional, could be just as much part of the seduction as her body is woefully ignored. A condensed, pedestrian translation by Christopher Cowell only helps dampen the delivery.

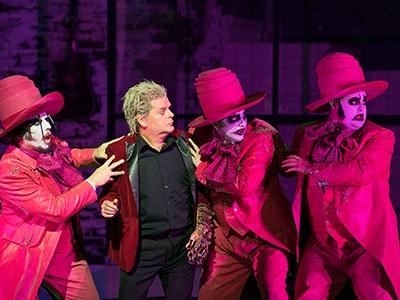

Alfons Flores’s set design better understands the old adage, managing more with less. Aided by smoke and primary reds and blues in Bruno Poet’s lighting, Flores’s dusty ground and a handful of props effectively conjure a purgatorial space reminiscent of Beckett.

But no existential discourse here, chimpanzee-like soldiers teem across the stage in their sunglasses, molesting on sight and hoisting a nameless female body up their phallic flagpole. In the climactic encounter with Don José, Carmen is stuck as Traumatised Barbie in a pink dress, matching accessory clutch and one limping high heel; just another victim in a series of rampant male aggressions.

In attempting to make his commentary relevant though, the Spanish director sacrifices too much. As a role, Carmen has inherent gravity. Many greats have shied away from its intimidating acting demands, even Callas only ever dared a studio recording and for better or worse, watching a woman encourage and taunt men’s advances like a toreador should give the part extra electricity in the #MeToo era. Instead, Bieito deliberately reduces her to a chauvinist cardboard cutout so that the biggest presence left on stage is his own.

Watching in the week of Weinstein’s imprisonment, this 2012 revival just falls on the wrong side of uncomfortable. Perhaps this speaks to the shelf life of rep productions at the ENO. The return of Jonathan Miller’s 1986 Mikado last season felt equally off-key, but with the emotional dance at the centre of this opera removed the rest of the evening follows perfunctorily.

A swaggering Ashley Riches is one of the more likeable performances though the baritone doesn’t muster sufficient power to convince as toreador Escamillo. Nardus Williams’s crystalline soprano would have made for an accomplished ENO debut without the skewed characterisation of Micaëla, sex-starved and spitting.

David Butt Phillip’s Don José swells in fits, his tenor vocals occasionally vigorous as he struggles with a frantic mix of needy and psychopathic acting; though to his credit, he only has two performance to find his feet, replacing Sean Pannikar for the tail-end of the run.

The chorus’s otherwise consummate singing is spoilt by Mercè Paloma’s distracting miscellany of costumes. Brit-Abroad gypsies mix with children clothed in charity shop finds so that there’s little consistency to the Franco-era Spain.

Valentina Peleggi conducts with a lightness of touch, the orchestra keeping Bizet’s score lively without overpowering the singers on stage, though this subtle delivery does not chime with Bieito’s desire for shock.

Overall the various parts of this revival fight against each other in search of another way to keep the blood pumping without a heart.