ENO Response: Luisa Miller reviews (Part II)

27th February 2020 in News

ENO Response is a new scheme that gives aspiring journalists and reviewers the opportunity to produce opera reviews and receive writing advice and feedback.

ENO has had no editorial input in the reviews. All views are their own.

Alex Grant-Said

It’s been seventeen years since Luisa Miller was last staged in England. Famed soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn was returning to the ENO in the title role after her long absence from the opera world. The stage was set for a good new year opener.

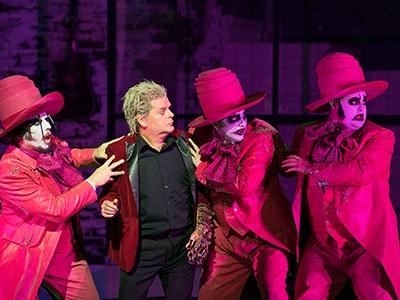

Unfortunately, it was set with parts from an entirely different production. Steel drums, Day of the Dead revelers and the straw-man effigy were initially intriguing but by the interval, I was still wondering why they were there.

A pity since this opera isn’t short of the right ingredients. It may not have the full romantic thunder of later Verdi classics such as La Traviata or Rigoletto but its final act can still send shivers down the spine and a punchy orchestra under Alexander Joel’s conductorship promised to deliver right from the overture.

Likewise, the libretto, based on Schiller’s Intrigue and Love, is a centuries-old proven hit with audiences. Essentially Romeo and Juliet with a class divide, we know these characters as soon as they come on stage: the innocent country maiden, the lovesick aristocrat destined to wed another, his tyrannical father and scheming servant. They are roles richly defined in our Romantic storytelling tradition.

Less clear is Barbora Horakova’s attempt to pair them with psychological thriller tropes. A mob boss version of Count Walter disposes of his near-naked victim in plastic sheeting, the murder watched by a child double of his son Rodolfo. Later a teddy bear’s downy guts are ripped out. Additions such as this lend a realism to the tragedy but feel tacked on, particularly with the opera’s central constraint removed. There is no identifiable setting to a romance that relies on social context.

Instead of supplying a compelling alternative to 17th Century Italy Horakova opts for the bare white box, the overfamiliar territory of any production reaching for ‘relevant’ and ‘modern’. It’s a surprisingly cliché approach given the young director’s rising star reputation and one which garnered her a spattering of boos come curtain call.

The audience is given Wurm in an attempt to make up for the lack of mise en scène. Behind Alex Lieberman’s stark set design is the idea that the count’s creepy henchman represents primal evil, the darkness inside us all. Virginal white walls are progressively defiled with black paint and graffiti as his lies take hold, driving Luisa and Rodolfo further apart. This very literal spreading – or rather smearing – of evil across the set is carried out by a slithering contemporary dance gang which seems the ENO accessory of choice lately having appeared in both Daniel Kramer’s Mask of Orpheus and Wayne McGregor’s Orpheus and Eurydice; though arguably to better effect than here.

If Wurm’s manipulations – think dungeons and forged love letters – are too baroque to be universal, Solomon Howard at least plays the role sufficiently sinister. The American bass is vocally exceptional, clear and rich with every syllable even if he’s made to spend much of his time leaning against a wall in black leather, dragging on cigarettes (because he’s the bad guy.)

Matching him is a first-rate assemblage of singers, each of whom could deliver the standout performance in another show. Olafur Sigurdarson as Miller and James Creswell as Count Walter are equally imposing. Mezzo Christine Rice dazzles despite a very brief appearance as Duchess Federica and Elizabeth Llewellyn proves her world-class reputation, building momentum toward Luisa’s rollercoaster finale where her warm voice surges to fill the Coliseum. It’s David Junghoon Kim though, making his ENO debut who’s truly unforgettable as the tortured Rodolfo. There is something of a young Pavarotti about the tenor’s sincere performance. His thrilling voice is paired with a lightness of step and compelling acting. In spite of a tepid production, the presence of all this vocal talent on one stage just about makes it worth braving rainy winter nights to see.

Tacita Quinn

Director Barbora Horáková’s interpretation of Verdi’s Luisa Miller is a bold statement on the dangers of toxic familial relationships, exploring where childhood trauma rests in the lives of adults and wreaks havoc. A tragedy of considerable scope, the libretto was based on the Friedrich von Schiller play Intrigue and Love. The class tensions that are so present in Schiller’s play and in other productions of Luisa Miller are almost nowhere to be found in Horáková’s vision. Instead, the production focuses on relationships between fathers and their children, the damaging influences of too much or too little love, and how this can damage familial relationships. Luisa, sung flawlessly by the brilliant Elizabeth Llewellyn, and Rodolfo, performed by David Junghoon Kim, are in love, but both of their fathers resent the pairing for different reasons. Luisa and Rodolfo’s childhood selves are incorporated into the production like spectres of enduring emotions. Horáková’s piece was an interesting interpretation, but it would have been still more powerful to further explore the tensions between middle-class and upper-class relationships in a modern setting. Overall, though the performances were superb and some of the visual imagery was successfully striking, the piece lacked depth. It is a shame that this production, adapted from Horáková’s 2018 production of Luisa Miller in Germany, did not capitalise on the climate of political and social hostility in Britain today.

Luisa Miller begins with a celebration of Luisa’s birthday by her father (Olafur Sigurdarson) and the townspeople, during which her father expresses concerns over Luisa’s lover Carlo. It later transpires that Carlo has been lying about his identity, he is actually Rodolfo, the son of Count Walter (James Creswell). Wurm (Soloman Howard) who works for Count Walter, and who wants Luisa for himself, tells the Count about the relationship. The Count then orders Rodolfo to marry Federica (Christine Rice) who has loved Rodolfo since they were children. This tangled state of affairs, which includes the imprisonment of Luisa’s father, eventually forces Luisa to lie about her love for Rodolfo because it is the only way her father will be released from prison. Rodolfo poisons Luisa because of his pain, but in death, she is released from her lie and admits that she loves him. The opera ends with the couple dying side by side, with their fathers looking on at the pain they have wrought.

Although La Traviata or Rigoletto are arguably more popular than Luisa Miller, the score for this opera is still delightfully entrancing. It is often associated with the start of Verdi’s ‘middle period’ when his most successful operas were written. It is a confident work that beautifully expresses lightness in moments of joy and deep intensity in moments of despair. Every note is dramatic, and the powerful score is done justice by Martin Fitzpatrick’s translation of Salvador Cammarano’s libretto. The music in this production was superb and extremely moving, enhanced by the diligent work of the conductor, Alexander Joel and the magnificent performers.

Llewellyn brought genuine fierce intensity to the role of Luisa, her deterioration from an innocent young girl to a damaged and heartbroken woman was captivating to watch. At the beginning of Act III, Luisa enters the stage and she begins to wash and tear at her skin as if ridding herself of the evil of Wurm’s touch. The chorus women join her dressed in black veils as if mourning the death of Luisa’s innocence. It was a theatrical moment not to be forgotten quickly, as one found oneself in awe of a spectacle of solidarity for the victim of non-consensual behaviour. It was one of the most moving moments in the performance. Llewellyn was well balanced by Sigurdarson as her overprotective anxious father and by Howard as the evil and manipulative Wurm. Unfortunately, there was little chemistry between Llewellyn and Kim, making the last Act more than a little bit of a drag.

The set and costume design, by Andrew Lieberman and Eva-Maria Von Acker respectively, varied considerably in success. Although the gradual additions of graffitied black paint on white walls was very striking, the space usually felt too big and too sparse. The costumes, especially the chorus costumes, were particularly thought-provoking, but the costumes for the main characters felt shallow and under-thought. The set and the costumes occasionally worked very well in harmony however, creating some stunning visuals that worked well with the score. The final moments of the play where Luisa is carried off by balloons perfectly illustrated Horáková’s vision for the production.

Horáková’s interpretation of Luisa Miller is a thought-provoking piece that concentrates on familial bonds and relationships. The constant presence of Luisa and Rodolfo’s childhood selves became the emotional centrepiece of the production, and this was carried off successfully. For Luisa, the presence of her childhood self highlights her loss of innocence and her deeply harboured feelings for Rodolfo. Contrastingly, for Rodolfo, the presence of his childhood self reveals his enduring heartbreak over his father’s crime, and his subsequent impulsivity and suffering. Though the use of childhood versions of Luisa and Rodolfo was not exactly subtle or original, it did help to create a more accessible production of Luisa Miller, one that explores the complexities of familial relationships. The production is worth seeing, especially for Llewellyn’s heart-breaking portrayal and beautiful interpretation of Luisa Miller.