ENO Response: Madam Butterfly reviews

2nd March 2020 in News

ENO Response is a new scheme that gives aspiring journalists and reviewers the opportunity to produce opera reviews and receive writing advice and feedback.

ENO has had no editorial input in the reviews. All views are their own.

Daniel Shailer

Seeing Madam Butterfly for the first time, it’s clear why this production is a fan favourite. It’s passionate and beautiful in a direct, striking way – with all the set-piece confidence of a slick West End musical. If anything, such a consummate production rather shows up such a difficult opera. In between a handful of anthologised favourite tunes, the plot is at best pretty lightweight, and at worst damningly problematic.

For a composer who once wrote: ‘I hate places! I hate capitals! I hate styles!’ Madam Butterfly is a creation very invested in foreign setting and nationality. It’s a presentation of Japanese culture that deals in binaries and stereotypes, intersecting with the particularly nasty misogyny of exoticism and fetishized otherness (did I mention Butterfly is fifteen?). Puccini is too invested, really, to excuse these elements of the opera as just fashionable or merely a representation. If one were to imagine a Venn-diagram of possible prejudices, Madam Butterfly hits it pretty squarely in the middle. Much of this comes to centre on Pinkerton and I wonder how Puccini’s creation was received on opening night; at the Coliseum today, he’s the object of pantomime boos. I think the cinematic perspective is probably important in this regard: Lieutenant Pinkerton is clearly a student of the 007 school of hit and run philandering and Michael Levine’s sloping, mirrored set frames the stage like a giant camera lens.

The more interesting insights are into the mythology of the United States – America’s dream and despair seen afresh in Cio-Cio-San’s eyes. As if sampled moments of the ‘Star-Spangled Banner’, weren’t enough, Pinkerton’s first names are Benjamin Franklin. It’s a presentation of nationality just as stereotyped as Puccini’s Japan, but it stands in a tradition of the fallen American dream: Pinkerton appears in spotless white uniform for his wedding, but by his inglorious return years later the same uniform has turned black. The naïve, exotic love interest and the careless Yankee: these are depictions of problematic stereotypes and it’s questionable whether in staging them, Puccini – and any production – is endorsing, criticising or (probably) something in between. At times, though, it feels like there’s a danger of reducing these harmful stereotypes of culture and gender to entertainment just a little too glibly.

This is all an issue only because it is such an entertaining evening. If the inherited elements of Anthony Minghella’s award-winning production weren’t enough, the performances are stellar. Natalya Romaniw in her role debut as Madam Butterfly is outstanding – the endings of longer notes sometimes want a little more care, but her vocal quality is excellent and finds a suitable balance of fragility and honest, innocent intensity for effective characterisation of the titular role. The whole production is well cast and there are no weak spots in a very balanced ensemble. For the sake of such vocal talent, it’s frustrating that the diction suffers and those in the audience without a view of the surtitles will struggle. That said, much of the staged drama is more emotionally than plot-driven (read ‘not much really happens’), so most of what needs communicating is in the music, with or without any deciphered words.

The set, such as it is, shifts from Pinkerton’s mansion to a starlit sky effortlessly. Oriental clichés, authentic Japanese dance and puppet theatre, and cinematic stylisation all mix onstage. But there never feels like too much is going on; efficient and striking, it feels iconic even as various moments continue to unfold. If you haven’ already, it’s worth coming to see Madam Butterfly to settle for yourself whether this roundly excellent production can justify quite such a difficult and sometimes dull story.

Patrick Shorrock

The awfulness of America’s current president only makes Puccini’s Madam Butterfly seem even more timely in its skewering of American colonialism and that brutal sense of entitlement to exploit that comes with western capitalist patriarchy. American sailor Pinkerton thinks a Japanese wedding to a 15 year old geisha is a purely commercial, entirely temporary transaction that he can tear up once he is ready to marry his ‘proper’ American bride. Butterfly, on the other hand, thinks she is getting a full American marriage with all the trimmings and that his commitment is permanent as hers. As usual in these situations, the woman dies but gets to sing gloriously before she goes.

This is very much a westernised view of Japan, with lots of exotic colour and a degree of cultural appropriation, but its criticism of western behaviour is lethally accurate and doesn’t come with any excuses – apart perhaps from the intoxicating act 1 love duet.

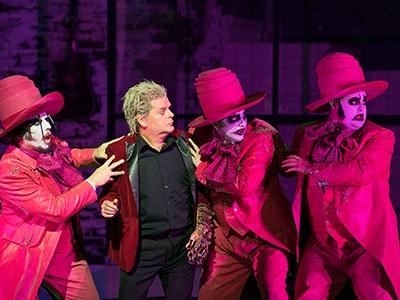

Pinkerton’s casual racism and unabashed exploitativeness are wince-making, in probably the world’s most unsympathetic Italian tenor role ever, but all too convincing in David Parry’s translation relayed in brutal clarity by the surtitles. After heedlessly causing emotional havoc, he refuses to take responsibility for it, and finally demands that everyone sympathise with him when he finally starts to realise the damage he’s done. No wonder that Dimitri Pittas gets good-humouredly booed at the curtain call, although this is for his caddish behaviour, rather than his singing, which was perfectly fine, although a bit brash with the top notes (dramatically in character, if musically unsubtle).

The programme correctly points out that Puccini was not exactly a feminist – and far from a good role model when it came to his own treatment of women – but his identification with Butterfly is so complete, without a hint of blame or patronising condescension, that the audience is completely on her side, and made completely aware of the power imbalance, racism and entitlement that enables the ghastly Pinkerton to ruin other people’s lives with no self-knowledge or emotional maturity.

The music has Italian warmth and lyricism in plenty, but there is a complex interweaving of leitmotifs that beats Wagner at his own game. The Japonisme – like the “Chinese” harmonies in Turandot – makes the score far more complex and interesting than its deservedly popular label might suggest. Puccini is a criminally underestimated composer.

This is certainly a very fine performance. Natalya Romaniw is extremely appealing and has the incompatible ingredients of strength, sweetness, and weight that this fearsomely demanding role requires. Her voice is just wonderful and deployed with gorgeous rock-solid technique. To be hyper-critical, there is a certain blandness in her stage presence, as there is in Martyn Brabbins’ conducting: he gets lovely playing from the orchestra and is unobtrusively effective – there is something badly wrong if you notice the conducting! – but I have known performances that were more overwhelming and searing. This is all a bit well behaved.

Having three intervals also undermines the intensity. Act 2 without an interval is a long emotional ordeal that leaves the audience utterly drained, as it should be. This was a bit too painless.

Part of the problem was Anthony Minghella’s over-elaborate production, which provides a visually seductive spectacle at the expense of dramatically effective support. There is a whiff of bad old-fashioned opera, and spectacle for its own sake, although perhaps I’m being hard on it for daring to replace Graham Vick’s wonderful production where the visual splendour always had a dramatic point and a theatrical meaning. Roderick Williams and Stephanie Windsor-Lewis are a bit subdued as Sharpless and Suzuki but don’t get a lot of help from the production.

Minghella is often needlessly distracting, with a long pause for dancing before the music starts at the start of act 1, and the Chinese lanterns moved by intrusive puppeteers in black during the act 1 love duet. Worse still, in act 2, the hapless infant Sorrow is a puppet, which means yet more distracting upstaging by the puppeteers. The low point was having 6 men walk across the stage and lie down just before the flower duet with plastic blooms attached into their cloaks so that Butterfly and Suzuki could pick them from their backs and gather them up and put them on Pinkerton’s very un-Japanese chair. That the performance could recover from these unfortunate touches shows just how good it was, but it really deserved a more intelligent production.

Aine Kennedy

ENO’s Madam Butterfly was somewhat reminiscent of a good takeaway: lurid-hued, dubiously authentic, and ultimately very satisfying.

‘What a farce this horde of friends and relations is,’ observes Pinkerton in the first act, as a troupe of kimono-clad women settle into a kneeling position stage left. He has a point. For all its promises of ‘bringing Japan to the London Coliseum’- and the programme’s rebuttal of ‘calls for the opera industry to become more diverse’- it is undeniably weird to see a flotilla of Caucasians bowing and fan-dancing like nobody’s watching. Anthony Minghella’s Olivier Award-winning production is visually stunning and dramatically effective, but, in the spirit of sensitive debate encouraged by the programme, it is surely worth noting a few ironies thrown up by the staging.

Several Japanese elements- costumes by Chinese designer Han Feng, set design by Michael Levine, and bunraku-inspired puppetry from Blind Summit Theatre- are combined to evoke the distant setting of Nagasaki in 1904. The artistic decision is extremely successful in portraying Puccini’s vision of Japan- the vision of an Italian man writing at the turn of the century, with no firsthand knowledge of the country. ENO’s programme observes that Westerners likened Japanese women to dolls, due to their small stature and ‘porcelain skin’; there is a certain irony, then, in the fact that the only visibly Asian ‘characters’ in this production are the puppets. The maid, for example- named as ‘Sweet Odours’ in ENO’s translation- was child-sized, silent, and swiftly packed off stage. Rather, ahem, doll-like indeed.

Levine’s set is a minimalist vision of Oriental domesticity. With its lacquered floor, bamboo screens, and paper lanterns on sticks, it could easily have doubled for a stage version of Mulan. Alongside the unapologetically dramatic lighting by Peter Mumford, it made for a highly effective, and enjoyable, depiction of the opposing forces that tear Cio-Cio San’s life apart. Madam Butterfly is a story of the tension between the familiar and the unknown, the rational and the emotional, the individual and the community; the reductionist set reflects both the stark, simple power of the forces at work and the cultural context in which the opera was conceived. It was, however, interesting to see how Puccini’s orientalism had been modernised. One can argue that in Butterfly, while the physical setting is Nagasaki, there is a second emotional setting in the American fantasy-land which Cio-Cio creates, both at home with Pinkerton and in her own mind. Minghella’s staging encapsulated the production’s focus on the house- the ‘little corner of America’- as the centre of the emotional and dramatic interest, while the Japanese setting, and characters, were often reduced to providing visual interest, much as in Puccini’s original production. One memorable tableau depicted Pinkerton and Cio-Cio San preparing for bed while a kimono-clad mob glowered silently in the dark outside, sporting fluorescent checkerboard prints that wouldn’t have looked out of place on Billie Eilish.

While the Japanese-style costuming was generally effective, enhancing rather than distracting from the performances, an exception might be made for Goro, the sleazy, pimp-adjacent matchmaker. William Berger, writing in Puccini Without Excuses, observes anecdotally that Goro is usually portrayed in Western dress; this convention is perhaps born of audience discomfort at seeing a non-Asian singer portray an unflattering caricature of Asian masculinity. ENO’s production blesses Goro with a particularly ridiculous costume which blurs uncomfortably with his other ridiculous qualities; there is a faint notion of mocking the actor’s consciously pseudo-Japanese appearance alongside the character’s objectionable traits.

At the end of the day, though, with singing of this calibre I would have applauded if Butterfly had come on in a coronavirus containment suit. Natalya Romaniw, carrying the production as any titular Butterfly must, was well equipped with the vocal and dramatic technique necessary to depict Cio-Cio’s maturation into a tragic heroine. She was well-matched by Stephanie WindsorLewis as Suzuki, Butterfly’s maid, bringing a quiet intensity to another demanding role; the relationship between the two women is almost the inverse of that of Butterfly and Pinkerton, marked by shared femininity and devotion rather than masculinity and betrayal. Dmitri Pettas’ Pinkerton and Roderick Williams’ Sharpless were equally effective in depicting the complex, human embodiment of the America which looms so large in Butterfly’s mind, and in Puccini’s score.

The production had its eyebrow-raising moments, but on reflection, this may be no bad thing. Puccini’s opera is unquestionably a masterpiece, and also unquestionably a product of its time.

The consciously Orientalist setting, together with the English translation, encouraged the audience to engage with and question the issues explored in the work. There was an audible intake of breath when Cio-Cio San merrily announced that she was fifteen; Pinkerton received a torrent of pantomime-villain boos at curtain call. Madam Butterfly may not have won her husband’s heart, but she certainly won her audience’s.