ENO Response: Orpheus in the Underworld reviews (Part III)

31st October 2019 in News

ENO Response is a new scheme that gives aspiring journalists and reviewers the opportunity to produce opera reviews and receive writing advice and feedback.

ENO has had no editorial input in the reviews. All views are their own.

Daniel Shailer

ENO’s Orpheus in the Underworld is a very clear attempt to welcome unfamiliar audiences to opera. Pantomime interaction, references to militant veganism and pre-teen gaming (Fortnight) are thrown in with (and perhaps more accurately against) Offenbach’s score. Occasionally it comes off: a nod to sitcom pop-culture when we learn Orpheus and Eurydice ‘were on a break’. More often it misfires (Keel Watson’s commendable attempt at a Scottish God of war) and is sometimes patronising. It is a quibble, but also part of larger trend, that the programme reads as if for a school group; billing Aristaeus as ‘(all will be revealed)’ does relatively little to clarify the plot for newcomers and doesn’t add much. Purists will be most surprised by the frequency of spoken dialogue. It helps bring clarity to the plot, but as a way to gather new audiences seems bound to misfire. What separates opera, nuts and bolts, from the West End is continuous music facilitated by recitative. It is not prescriptive, then, to criticise Rice’s decision to trade away an important element of musical continuity, the patience of stricter buffs, and Opera’s USP in an effort to entice newer audiences perhaps already familiar with musicals.

It’s a well-meaning effort, and indeed one appropriate to Offenbach’s opera. The composer’s appropriation of popular dance for his galop infernal perhaps go some way towards validating modernisation – a freer translation of source material to communicate a more truthful essence of the original’s recognisable cultural appeal. In this regard, Tom Morris’ lyrics strike the balance perfectly. Raucous, erudite and witty, they are a clear highlight; they show variation too, from Orpheus and Eurydice’s riotous bickering in Act One, to a deliciously dark dance-until-you-drop closing chorus.

Rice’s production worries away at a balancing act at the centre of satire: a tussle between stereotype and flippancy. During the overture Rice adds a dumbshow backstory to Orpheus and Eurydice’s relationship. In scenes lifted from Pixar’s Up, we watch the innocence of first love shaken by a miscarriage – to a backdrop of colourful balloons. We are introduced not to the matrimonial trope Mr and Mrs Fawlty, but a young couple struggling to deal with grief; from the outset, Rice is determined to raise the stakes of Offenbach’s satire. So at the conclusion Mary Bevan’s final can-can is not an acrobatic caper, but jerks and convulsions of hellish agony.

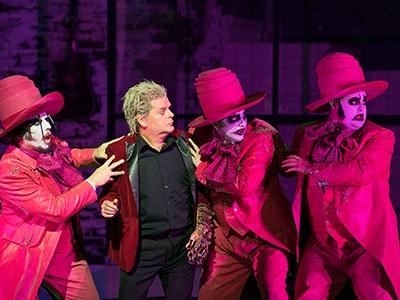

There are plenty of compelling moments. Alex Otterburn is captivating as Pluto: a gyrating mass of sequins and leather. The god of the underworld’s enormous sexual deviancy seemed to play upon his lips in a constantly flickering smile. Lizzie Clachan’s set design also stands out. In Olympus we find a heaven that is washed up and bored; the immaculate tiling of a glam swimming pool is no longer Gatsby’s party-mansion, but a tired public lido. The Greek gods are given a similarly seedy treatment: too much leopard print and pimpish silk dressing gowns meet in Lez Brotherstone’s delightfully brash design. The contrast with Orpheus and Eurydice is pointed, also; the lovers are decidedly working-class, in plait shirts and rolled up jeans. It’s a lumberjack image of bucolic innocence that puts Orpheus out of place among the expensive (if trashy) gods. Jupiter’s cruelty, we feel, is not only borne of masculinity but of class privilege also.

The production comes into its own when staging performances of male vulnerability. Indeed, performances are precisely what Rice shows us: from Orpheus’ doe-eyed sensitivity (‘I’m a man of feeling’); via John Styx’ drunken lament of a wasted life; to Jupiter’s metamorphosis into a vibrating fly. We are asked to examine these men together so that Jupiter and Orpheus’ emotional manipulation are thrust into the same light – the latter uses over-egged sensitivity to control Eurydice in a manner that is perfectly symbolised in Jupiter’s harmless fly. Rice almost overshoots her mark in this regard. How satisfied can we be with the relationship Eurydice is returning to when she tries to leave Hades? Playing their argument in the first Act up for laughs, Lyon occasionally becomes a hero that is slightly too gormless.

Orpheus in the Underworld is certainly exhilarating – carried by standout performances and enthralling design. It falls over itself, however; trying too hard to engage the audience, it comes across self-conscious and often patronising.

Olivia Clark

Jacques Offenbach’s work uses humour to point out the hypocrisy within the authority. Emma Rice’s adaptation is a whimsical abstract piece of art that captures Offenbach’s uses of humour to point out the hypocrisy within the authority, with a feminist stance.

Despite the running theme of abuse of power on behalf of the Gods, Orpheus trials of retrieving his wife back from the underworld and Eurydice’s self-destructive behaviour. The aesthetic and playful scene made the cast appear to have a hoot of time acting in the play which was emphasized by a choice of cast that perfectly suited the roles they were playing.

I found that the prologue of Orpheus and Eurydice’s life before they lost their child and the interferences of Pluto before the opera began a sweet touch, as it really made me sympathize with the couple. It was made clear to us that they both went through a traumatic event, which changed their perception of each other. They remembered what it was like to be together. However, they weren’t able to repair what had happened. By doing this Rice successfully encourages us to be hopeful that they will fall back in love with each other, which I suppose that is what we hope for.

In my introduction previously, I stated that Offenbach and Rice used the Gods to point out the hypocrisy in authority. In this case, the Gods Jupiter and Pluto are those people. Their power, immortality and divinity have made them believe that it’s ok to be perpetrators of misleading, manipulating, and raping. It is because they have the status and power to get away with it. This brings home to me the” Time’s up” and the “#Me too movement”.

Even so, watching what Euridice was going through was very uncomfortable he plays was dated in its humour but still made us laugh. Which upon reflection I realised. Pluto in disguise as the shepherd was taking advantage of a woman who was full of grief, Jupiter once again shapeshifted into have sex with her and she was sold off to become the sex slave of Bacchus (Dionysus). At the end of the performances, we see Euridice dancing to the tune of the can-can in a state of mania and you could feel her pain.

I wonder why Offenbach used the Roman names of the Gods in a story that is based on a Greek myth considering that his audience when it first came out would have been more familiar with the differences between the Greek and Roman pantheon and the continuation of the Romanised names bothers me because it’s a Greek tragedy and it would make more sense for the Greek Gods names to be used.

Act ll, introduced us to Mount Olympus, the gods and set the scene for the rest of the Opera. This included Juno, Pluto, cupid, Diana and Venus calling out Jupiter, because he abused his power. Sadly, this was slightly marred by Venus appearing to struggle with her coloratura.

Why does whoever plays Satan or in this case Pluto have to act camp get a few laughs? I feel it’s an overused characterisation of being camp.

I found their use of balloons very imaginative. They used throughout the show each coming back as a new object. At first, they were clouds, then sheep, a means of transportation, a skirt and finally a disguise. I think the fact that they were mostly matt white balloons meant that it was a great way to reflect light on them to enforce their desired effect such as the purple lights shone on the balloons at the bottom of the stage to give the impression of depth and/or the underworld during the beginning of Act ll.

I loved the mock ballerinas with balloons tutus and white bodysuits. The whole characterisation of a cloud dancing and having its own personality was funny especially as they seem to be captured by the smallest thing. I feel that the morph suit given to the performers should have also been given undergarments for support and less obvious underwear lines.

I didn’t like the jumper worn by Public Opinion, it seemed out of place for the period. Rather, I think that the character would have looked more in tune to the era if it were a bit more like a casual suit with the cap. Similarly, the clothes of the background characters particularly the women suggest that it was set in the 60s rather than the late 50s although I got a strong old Hollywood vibe from all the god’s beachwear and evening gowns.

All in all, this was a spectacular production with an eclectic stage production and costume design which worked very well. This worked well, the audience participation showed that Rice could bring to life the dated humour, not lose the essence of the French original. Her wacky interpretation brought it together.