ENO Response: The Marriage of Figaro reviews

17th March 2020 in News

ENO Response is a new scheme that gives aspiring journalists and reviewers the opportunity to produce opera reviews and receive writing advice and feedback.

ENO has had no editorial input in the reviews. All views are their own.

Patrick Shorrock

The Marriage of Figaro has received some fine productions at ENO over the years, from Jonathan Miller, Graham Vick, and Fiona Shaw. This latest one from Joe Hill-Gibbons, with a superb ensemble of singers, is a delight and one of the best.

His production gets rid of all the clutter – even the Act 1 chair on which Cherubino is discovered. The lack of silly business and cheap laughs enables a deep focus on the characters and is clearly relished by the audience, as the stage action arises from the music and the drama, not from the need to fill a void with distractions or sight gags. Designer Johannes Schutz’ white box with four doors adds to the feeling of intimacy and claustrophobia, as does the cast’s extreme physical proximity to one another – something that seems far more convincing than the usual spacing them across a vast stage that is far too big to be even an aristocrat’s house. This production shows how, if you know what you are doing, you can make even the vast space of the Coliseum feel intimate.

There is always plenty going on – it’s just that it is always illuminating. Full and hilarious use is made of the four doors on the white box set that instantly open and shut with immaculately choreographed timing that is gloriously aligned with the music. Characters appear on stage when they aren’t there, but are being talked about. This sounds crude and alienating, but it is done with a wonderful lightness of touch that brings the characters’ thoughts brilliantly alive to hilarious or troubling effect, whether it is the Countess and Susanna both making love to the Count during their letter duet, or the Count glimpsing everyone else but him having sex in jealously green light. Hill-Gibbons is aware just how ambivalent and subtle this piece is. It may resemble a sex farce – as is shown by the way the set’s four doors fit the action so well – but it has a troubling, hilarious, and finally profound light to shed on the difficulties inherent in human interaction, where every confrontation is skewed by a power imbalance whether sexual, financial, or social, and every motivation is ambivalent, and desire is not always for one person: Cherubino says he has the hots for everyone, while the Count is after Barbarina as well as Susanna, but the Countess is more attracted to Cherubino than she should be, as is Susanna to the Count. And Susanna starts off horrified at the idea of Figaro being jealous, only to take pleasure in tormenting him in Act 4, while Figaro himself must have got quite flirty with Marcellina to get her to lend him money on the security of a possible future marriage.

Kevin John Edusei’s conducting puts plenty of fizz in Mozart’s musical champagne -letting the music breathe whilst progressively increasing the momentum. This is the best kind of unobtrusively right conducting. Bozidar Smiljanic is a more low-key Figaro than usual – surely part of the point is that he is not hopelessly at the mercy of his own testosterone in the way that the Count and Cherubino are; he can’t afford to be. It is a relief not to feel garrotted by the force of his personality, which is so often (mistakenly) thought to be what the part requires. Louise Alder is an independent and fiery Susanna, but nicely sung. Jonathan McCullough is sexy and magnetic as the Count, but isn’t afraid to look ridiculous or unsympathetic, as he gets increasingly frustrated as he discovers that good looks and privilege aren’t enough to enable him to have his way with every woman he fancies, and don’t prevent him from being a selfish prat. Hannah Hipp is a wonderfully brattish Cherubino, who is clearly making the same assumptions about women as the Count. As the Countess, Elizabeth Watts – clad by Astrid Klein in a way that seems designed to be reminiscent of Princess Margaret – is perhaps rather too sumptuously voiced and grandly phrased. At its best, her singing was absolutely glorious, but less (and a more straightforward kind of vocal delivery) would have been more. Susan Bickley Andrew Shore and Clive Bayley were all luxury casting.

It’s a brilliantly musical production, whether it is Countess and Susanna dancing to Voi Che Sapete – where choreography brilliantly fits the music’s rhythm while very effectively loosening everyone’s inhibitions – or the manic farce that goes on during the overture. I’m usually irritated when this piece is done out of period, as its references to abolishing the droit de seigneur make no sense today, but the huge gains here outweigh the small losses. Jeremy Sams’ translation fits the music well and is clear and witty, even throwing in a Rousseau gag. Just marvellous.

Tacita Quinn

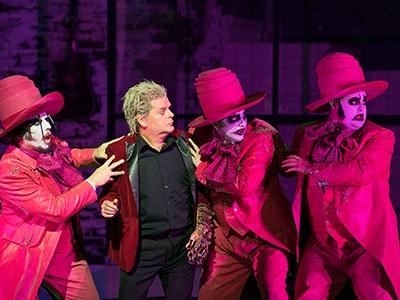

Mozart meets Michael Frayn in ENO’s production of The Marriage of Figaro. If one wants a farcical distraction from modern woes this is the opera to see. Director Joe Hill-Gibbins’s interpretation is an energetic, door-slamming, axe-waving, skirt-swishing drama, that presents Mozart’s wonderful score in the form of a quintessentially British farce. The libretto is cheekily littered with familiar phrases, bringing to life the obvious comedy provoked by the story and is spectacularly presented by the cast. Louise Alder, playing the character of Susanna, with her sharp wit and cool condemnation in tandem with her jaw-dropping voice, practically stole the show, rarely was my attention severed from her fabulous performance. The sleazy philanderer Count Almaviva is the perfect villain, knowingly played by Johnathan McCullough, his frustration and ridiculousness akin to John Cleese’s Basil Fawlty.

Hill-Gibbins mainly kept the production apolitical, but the Count nonetheless gets his just desserts in line with the #MeToo era. The production, unfortunately, does dip in the third and fourth Acts, when the tight staging gives way to a much wider space with a very limited set, which is incongruous with the rest of the piece. Overall, however, this is a thoroughly enjoyable production, filled with gaffs, snogs and drama. Once again, The Marriage of Figaro proves itself to be completely timeless, allowing young directors to continue in the tradition of Mozart, whilst also providing the wit and cheek to make an old story invigorating, exciting, and fresh.

Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro was first performed in 1786. The libretto is based upon a play of the same name by Pierre Beaumarchais and was originally written by Lorenzo Da Ponte. The translation of the libretto was undoubtedly one of the highlights of the performance, working well with the other aspects of the piece while allowing performers enough space to bring their own characters to life. In this production of one of the most popular operas of all time, the curtain opens on an entirely white set, with four consecutive doors, only about three metres away from the opening of the pit. The set, designed by Johannes Schütz, at first seemed tight and claustrophobic, but it lent itself well to the physical comedy, and the plainness imposed a sense of timelessness that worked well with the apolitical interpretation.

Mozart’s famous overture kicks off Act one, as the performers present themselves weaving in and out of various doors seemingly leading to nowhere. The audience is quickly introduced to Figaro, sung by the smooth Bass-Baritone Božidar Smiljanić, and soon the wonderfully complex plot is underway. The opera begins on Figaro and Susanna’s wedding day, and the drama that ensues is based on many of the additional characters being intent on separating the pair. The first Act, which sees the count propositioning Susanna, also discloses the conspiring of Doctor Bartolo (Andrew Share), and Marcellina (Susan Bickley). Additionally, the audience is introduced to Cherubino (Hanna Hipp), who has been dismissed from court for being found with Barbarina, sung by Rowan Pierce. I usually find the breeches role in opera a little crass, but Hanna Hipp gives a very refreshing interpretation, it is full of life and licentious energy without being too churlish.

Acts one and two of this performance, are near spotless. There were, however, some inconsistencies between the chorus and the pit at times, which is unfortunate, but this also could have been due to first night nerves. Acts three and four were less enjoyable than the first half of the performance. Energy seemed to dip in the third Act, with the exception of the encounter between Figaro and Marcellina, where he learns that she is in fact his mother, which was side-splitting. Act four was disappointing in comparison to the rest of the performance. Despite energy seeming to pick up again amongst the cast, and absolutely spectacular performances from Louise Alder and Božidar Smiljanić, the set change was wrong, cold, and far too sparse. It felt completely out of place with the rest of the performance and seemed as if it didn’t make sense in line with the plot, which is a shame, considering how successful the set was in Acts one and two.

The costumes for this production, designed by Astrid Klein, are all fun and glammed up to the max. They aren’t entirely timeless, but they don’t signpost specific political meanings, which has been a common trait in the other productions at ENO. The costumes did well to highlight interpersonal relationships and stereotypes, rather than impose an over-arching theme on the production.

This production is fast, intriguing and innovative, and is overall thoroughly enjoyable. It is a distinct break from ENO’s political streak and is quite refreshing. This is director Joe Hill-Gibbins’s main stage debut at ENO, and it is a considerable achievement, he is one to watch.