ENO Response: The Mask of Orpheus reviews (Part II)

11th November 2019 in News

ENO Response is a new scheme that gives aspiring journalists and reviewers the opportunity to produce opera reviews and receive writing advice and feedback.

ENO has had no editorial input in the reviews. All views are their own.

Daniel Shailer

I arrived to The Mask of Orpheus fifteen minutes late after misreading train timetables. Only after several moments of electronic pulsing and a wordless ‘passing cloud’ did I realise I had unwittingly chosen a surtitle free performance. So, when I learnt in the interval of a made-up ‘Orphic’ language it all felt a little like an elaborate in-joke at my expense. These are the questions indeed.

Birtwistle’s opera is a tottering construction of memory and myth. It feels Joycean and complexity is not only its vehicle but its subject also (a dense, five-page synopsis is testament to the fact). In light of this, Daniel Kramer’s gaudy, overburdened design might work as a visual insurance policy against potential confusion. By way of a fortuitous gift from National Rail’s own brand of confusion, I was able to watch some of the performance from the dress circle and the rest returned to the stalls. So while for some of my neighbours in the latter this design was ‘grotesque’, others at the Coliseum agreed it certainly gave us something to look at. Ultimately it was too much, three iterations of one story – played out concurrently at giddying heights of abstraction – needed focus not distraction. But it demonstrates a more successful attempt than Orpheus in the Underworld to present a welcome face to the ENO’s new audiences. Decidedly not dumbed down, high-camp vibrancy and give a lifeline of visual interest to those of us for whom some moments where comprehensively baffling.

Kramer’s production is not entertaining. But it is not ever boring either; watching it feels like picking at a wound. Each time we witness the same memories played out the screw turns: when Orpheus the Hero hangs himself at the end of Act II, he reawakens after the interval to haunted memories of Eurydice and Aristaeus; each time Orpheus’ children (represented by an unending supply of dolls) are taken from him and violently destroyed it is painfully uncomfortable. Is this viciousness just for the sake of it? It can feel like that at times. Orpheus’ children are blended to a pulpy red gloop in a moment that seems particularly gratuitous, but in fact has horrifying significance when Orpheus reaches for a drink. The cooler ensconced in his Rockstar-pad produces more of the blood red cocktail each Orpheus has been drinking all night. A chilling paradox: his dead children return transubstantiate in the very alcoholism that took them away from Orpheus in the first place.

This show, then, is at its best when it reminds us of the human story at its centre. Matthew Smith’s aerial work as the Heroic Orpheus is mesmerising and, with Alfa Marks, he produces an immensely moving final moment of intimacy as the curtain lowers. Peter Hoare’s voice pushes at its immense limits to contain Orpheus the Man’s pain. Too often however, moments like these are lost in a swamp of glitter and confusion. We’re told eagerly about the however many crystals Daniel Lismore has borrowed for his costume design, but they only add superficially to the story being told. Hoare, crouched over a skull in his climactic scene of self-destruction, has to draw his hammer blows slightly short for fear of damaging a presumably expensive prop. This feels symptomatic of a production that leaves a powerful and impressive mark, but whose priorities are out of order. The greatest applause of the night went to Martyn Brabbins, his orchestra and Birtwistle’s exhilarating music.

Tacita Quinn

With only thirty seconds of catharsis offered by the embracing Orpheus and Eurydice at the end of the performance, I felt it was a significant achievement to have traversed Harrison Birtwistle’s three-and-a-half-hour epic myth that is The Mask of Orpheus. This trying but inspired production pays homage to Birtwistle, its cyclical structure is stylishly pulled off in what has, so far, been the most successful production in this season at ENO. The constantly changing and recurring opulent costumes by Daniel Lismore and the frenzied but poignant projections by lighting and video designer Peter Mumford, combine entrancingly with Birtwistle’s score. This is complemented by heart stopping performances from the entire cast, with outstanding operatic performances from Orpheus the Man (Peter Hoare) and Eurydice the Woman (Marta Fontanals-Simmons), alongside awe-inspiring dancing from Orpheus the Hero (Matthew Smith) and Eurydice the Hero (Alfa Marks). Although the visual imagery was fabulous, I could not help but feel that this was a piece of art rather than an opera. Although The Mask of Orpheus attracted a far younger (and trendier) audience than usual, it still felt inaccessible and above all self-indulgent. However, although the production was complicated and extravagant, reflecting the demands that this opera makes on its audience, the recurring moments of pain and joy made for a surprisingly hard-hitting piece.

The Mask of Orpheus is unlike any other adaptation of the Orpheus myth. Birtwistle wanted a piece that symbolised the fickle nature of mythology, deciding to portray multiple variations of Orpheus and Eurydice all at once, united in a cyclical adventure of love, loss, and revenge. The piece begins with the first story, where Orpheus-the-Man is reborn, he is reminded of his love for Eurydice, and goes to find her in the underworld. The second story sweeps the stage with the loveless and spiteful marriage between the protagonists, as Eurydice-the-Myth tackles Orpheus-the-Myth’s abusive nature. The final couple, Orpheus and Eurydice the heroes to be, glide across the stage in a tender rhythmic dance, in a performance that radiates affection and lust. All three performances happen simultaneously, in addition to several prominent subplots that are interwoven together through the score. The multifaceted style of the piece means there is no plot, it is all non-linear. If your main attraction to opera is drama you will not find it here, but although at points The Mask of Orpheus feels pretentious, it is an invigorating exploration of the extra-ordinary, of memory, of the human condition.

The skill needed to successfully pull off a production of this magnitude is staggering, and the performers do this spectacularly. Peter Hoare brings the broken and pain-ridden Orpheus to life, the quality of his voice being tentative and yet resilient. He is paired beautifully with Marta Fontanals-Simmons, whose warm rich voice is only upstaged by her performance as a whole, which has an irresistible air of dark sensuality. The highlight of the performances however were undoubtedly Matthew Smith and Alfa Marks, whose phenomenal movement to Barnaby Booth’s choreography was simply entrancing. The different levels of movement in this performance lent itself to Birtwistle’s score. Changes in the music often helped draw the eye to a particular story, the connection between the music and the performances was very impressive, especially for a modern opera.

No discussion of this piece would be complete without saying more about the costume designer Daniel Lismore’s weird, wonderful and nightmarish vision for this piece. The reconciliation between the classical imagery and the outrageous art school quality of Lismore’s design, delivered the magical surrealism that complemented Birtwistle’s music. One cannot help but think, however, that some of the decoration was unnecessary. Although it added to the dreamlike effect, the use of 400,000 Swarovski crystals made me wonder whether there might be cleverer ways of displaying godly nobility. On the whole, however, the costumes added a significant amount to my enjoyment of the piece and were a key part of the visual language of the performance.

Lizzie Clachan’s set for The Mask of Orpheus has been her most successful design yet for this season at ENO. The contrast between the Art Deco plain set at the beginning and what the set slowly became was surreal. The glass ‘prison’ surrounded by stairs, in combination with Peter Mumford’s projections, created a colourful mind-bending reality. It gave off a familiar but somehow disturbing aura, and really immersed the audience in the dream world of the performers.

Unfortunately, I found a great many aspects of the piece pretentious and inaccessible. This is not solely concerned with ENO’s production, but the subject of the piece itself and the type of opera that Birtwistle wrote. It is hard to connect with, and although this is no doubt part of the point, many people might feel estranged by the over-extravagant opulence and the self-indulgent character of the piece. Having said this, the moments of the opera where meaning is truly divulged are breathtaking. As the curtain closed, the utterly tranquil heroes Orpheus and Eurydice embraced, slowly twirling above in soft light, while confetti fell from above. It is worth seeing The Mask of Orpheus just for this moment of pure understanding and love.

Alex Grant-Said

Harrison Birtwhistle might not be most the mainstream of names but the 85-year-old British composer is often hailed as one of the most important of the 20th century. His Mask of Orpheus is something of a myth itself. Helming the seminal work are two prominent ENO figures: music director Martyn Brabbins as conductor and Daniel Kramer as director; who steps down as ENO artistic director once his Orpheus season is complete.

Both men are Birtwhistle aficionados – Kramer having begun his opera career in 2008 with Birtwhistle’s Punch and Judy – yet even they will have only ever been able to see The Mask of Orpheus just once before. A now fabled debut at the Coliseum in 1986 is all the opera has had. Since then it’s not been fully staged anywhere in the world. It’s remained a mirage, a memory – appropriate for a piece that plays with time, recollection and loss – until now. With this in mind and paprika nuts in hand, I took to my seat eager to experience opera history. But whether I dozed off or ingested a poisoned nut, what came next was a nightmare whose chaotic details grew fuzzy even as I watched. It was also a night of spectacular opera to remember.

The electronic rumblings of Apollo, Orpheus’s divine father, are a good introduction to Birtwhistle’s music. The god booms dramatic, incomprehensible, crisp from speakers occupying the Coliseum’s boxes thanks to arrangements by the late Barry Anderson. From there Peter Zinovieff’s esoteric libretto begins as a series of sounds, half-formed words made by Peter Hoare, a reborn titular Orpheus trying to remember who he is. Once he has finally learned to talk minutes later, Hoare quavers impressive tenor notes. And Clare McFadden as the Oracle of the Dead launches into soaring soprano trills with aplomb every time she appears, even if the clarity of her vocals are undercut by the comedic chirrups her role forces her to make. In fact, the singers are generally pinned down by Birtwhistle’s score, which is powerful but does not allow for lyric grace. The orchestra sustains its heavy dissonant punches almost too well and eventually, moments of silence comes as a relief.

Clever set and costume design help to make sense of the highly abstract non-linear events taking place on stage and mesmerise in the process. Lizzie Clachan’s impressive terrarium, blooming like a Garden of Eden as the show progresses, displays the aerial artists with a stroke of genius. And despite three separate versions of the Orpheus-Eurydice-Aristaeus love triangle sharing the stage, everyone is able to appear and disappear seamlessly. Up through the air – as with Matthew Smith’s aerialist Orpheus – downstairs for Marta Fontanals-Simmon’s grand Eurydice entrance, or sucked into their deathbed, for Peter Hoare’s feeble, dying Orpheus. Clachan’s sets are a masterclass in trapdoor concealment.

This is fortunate considering the surprising abundance of props used to transform the stage without set changes. So much of Kramer’s production is cast members bringing things on and off in remarkable quantities, getting in and out of clothes over and over again that it occasionally tips into fussiness. Some of the performers are clearly struggling, and the odd cable is surreptitiously kicked away time and again. But personally, this is preferable to sparsity. All the stops are truly being pulled out.

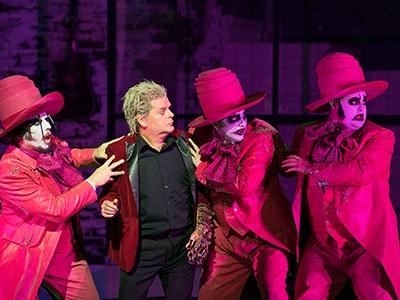

Daniel Lismore’s costumes are a demonic carnival, like Fantasia’s ‘Night on Bald Mountain’ with drag queens and bubblegum. They brilliantly offset the bad dream feel of the libretto with psychedelic horror. It’s impossible to turn away from a chorus of jiggly blow-up nurses and hellish mariachis. Lismore, channeling Jodorowsky, adds needed technicolour to Birtwhistle’s somber mythology and it must be said that those 400,000 crystals generously provided by Swarovski – mentioned on every piece of publicity – do sparkle oh so nicely under stage lights.

The spectacular overstimulation for both eyes and ears pushes the audience into a trance-like state like an evangelical exorcism. The Mask of Orpheus has to be given into. “It’s difficult grub,” Birtwhistle admits of his work in the programme, and it must be said that a few empty seats appeared during the first interval. By the second there were at least ten directly in front of me. For those remaining however, debate in the bar was alive and frenetic, a surprising sense of camaraderie appearing in the air and a standing ovation proving that the surviving audience had received rich rewards for sticking with it. I don’t think I’ll see another opera quite like it for a long time. And I’ll lay off the paprika nuts for a while.